Tue 7 Jul 2009

Immobilized by multiple injuries, ad manager keeps selling from hospital bed

Posted by DavidMitchell under General News, Inverness, Marin County, Point Reyes Station

[3] Comments

Linda Petersen, advertising manager of The West Marin Citizen, working from her bed in The Rafael Assistance for Living, a convalescent hospital on North San Pedro Road in San Rafael.

I’ve been posting periodic updates on Linda Petersen’s condition following her horrific traffic accident in Inverness June 13. Linda suffered 10 broken ribs, a broken arm, a broken leg, a broken knee cap, two broken vertebrae, two broken ankles, and a punctured lung when she fell asleep at the wheel and hit a utility poll along Sir Francis Drake Boulevard.

Since then, Linda has spent time in Marin General Hospital, Kaiser Medical Center in Oakland, and now The Rafael. She wears casts on both legs and on her left arm. Her head and neck are immobilized by a medical “halo” made of steel.

The halo won’t come off for at least four or five more weeks, and until then she is basically stuck. She spends a few minutes in a wheelchair each day, “but it’s not very comfortable,” she acknowledged Monday. “It puts a strain on my neck. This thing was probably invented during the Second World War and hasn’t been been updated since. It weighs a ton.”

Weighed down by the head gear, which is screwed into her skull, and able to move only her right arm, Linda has chosen to fight the tedium of spending a couple of months on her back by getting back to work.

Using her cell phone, she’s already working with about a dozen advertisers, she said, “and as soon as I’m online, there’ll be a lot more.” (Three days later following numerous calls to an ISP her laptop was finally connected to the Internet.)

How do merchants react when she calls them from her hospital bed? “They’re kind of surprised,” she replied. “‘Oh, Linda, how are you doing?’ they ask. ‘We’ve been worried about you. You sound so good.” Does their concern translate into ad sales? “It might give me a bit of an advantage,” she admitted with a laugh.

Linda has been receiving a steady stream of cards, emails, and phone calls from well wishers. People have brought her flowers, fruit, yogurt, ice cream, books, balm, and magazines. “I’m so touched by that,” she said. “The outpouring of encouragement has really helped me keep a good attitude.”

Linda’s much-beloved dog-about-town Sebastian died in the crash. Here the two of them paused while on a walk at White House Pool.

Speeding Linda’s recovery, her doctors say, is her being in good physical shape at 61 years old. Before her accident, Linda went to the West Marin Fitness gym almost daily. Until two months before the accident, she went horseback riding every week or two, and therein lies a story.

Linda lived in Puerto Rico for more than 20 years, and in March 2000, she was riding her own horse, a Paseo, when it was attacked by a much larger stallion. With the other horse trying to “throw itself” onto the back of Linda’s horse, she leapt off, only to have her horse fall and roll over her lower back.

Her injuries on that occasion consisted of a dozen broken bones, including a crushed pelvis, and numerous internal contusions. Despite major surgery and extensive hospitalization after the mishap, her hip was deteriorating by the time she moved to the Bay Area about five years ago, necessitating a hip replacement in 2006.

After recovering from that hospitalization, Linda resumed riding, accompanying friends on trails throughout Marin and Sonoma counties. Increasingly on her mind, however, was her recent hip surgery and the fact that our bones become more brittle and take longer to mend as we grow older. So two months before her automobile accident, “I decided I better not do anymore riding,” she noted, laughing at the irony.

And then the conversation turned to business. Shari-Faye Dell of The Citizen happened to also be visiting when I showed up at The Rafael, and Linda told her that ads for Osteria Stellina restaurant and Zuma gift store were ready for this week’s issue. “Check with Chris [Giacomini, the owner] at Toby’s,” she told Shari. “If he isn’t there, you can also talk with Oscar [Gamez, the feed barn’s manager].”

Later in the hallway I commented to Shari how remarkably Linda was handling a situation that would devastate many of us. “She’s one of those people whose glass is half full,” Shari responded with admiration.

This week I saw a wild turkey scare off a young deer on this hill by flapping its wings, and I’ve previously seen horses having fun chasing turkeys around in the Giacomini family’s pasture next to mine.

This week I saw a wild turkey scare off a young deer on this hill by flapping its wings, and I’ve previously seen horses having fun chasing turkeys around in the Giacomini family’s pasture next to mine.

In 2007, Marin County supervisors asked Senator Dianne Feinstein (right) to intervene after the Point Reyes National Seashore administration began harassing the oyster company.

In 2007, Marin County supervisors asked Senator Dianne Feinstein (right) to intervene after the Point Reyes National Seashore administration began harassing the oyster company. The conflict began with an

The conflict began with an  The first exposure occurred in July 2008 when the Inspector General’s Office of the Interior Department issued a

The first exposure occurred in July 2008 when the Inspector General’s Office of the Interior Department issued a  “That really is a policy and law issue,” said Jarvis (right), “not a science issue.”

“That really is a policy and law issue,” said Jarvis (right), “not a science issue.” This legal fact may in the long run be the main obstacle to the Point Reyes National Seashore administration’s machinations to close Drakes Bay Oyster Company three years from now.

This legal fact may in the long run be the main obstacle to the Point Reyes National Seashore administration’s machinations to close Drakes Bay Oyster Company three years from now. In 1974, when the Park Service wrote an environmental-impact statement for the proposal to designate 10,600 acres of the Point Reyes National Seashore as wilderness, the park noted that “control of the [oyster company] lease from the California Department of Fish and Game, with presumed renewal indefinitely, is within the rights reserved by the state on these submerged lands.”

In 1974, when the Park Service wrote an environmental-impact statement for the proposal to designate 10,600 acres of the Point Reyes National Seashore as wilderness, the park noted that “control of the [oyster company] lease from the California Department of Fish and Game, with presumed renewal indefinitely, is within the rights reserved by the state on these submerged lands.” National Seashore Supt. Don Neubacher would like to shut the oyster company down in 2012 when the use permit for its onshore facilities (at right) comes up for renewal, but the onshore facilities are also protected.

National Seashore Supt. Don Neubacher would like to shut the oyster company down in 2012 when the use permit for its onshore facilities (at right) comes up for renewal, but the onshore facilities are also protected. The field representative for Congressman John Burton (at left), who sponsored the legislation in the House of Representatives, was the late Jerry Friedman of Point Reyes Station, chairman of the county planning commission and co-founder of the Environmental Action Committee of West Marin.

The field representative for Congressman John Burton (at left), who sponsored the legislation in the House of Representatives, was the late Jerry Friedman of Point Reyes Station, chairman of the county planning commission and co-founder of the Environmental Action Committee of West Marin.

Here’s a poke at the kind of personal ads that show up locally in The Bay Guardian or on Craigslist.

Here’s a poke at the kind of personal ads that show up locally in The Bay Guardian or on Craigslist.

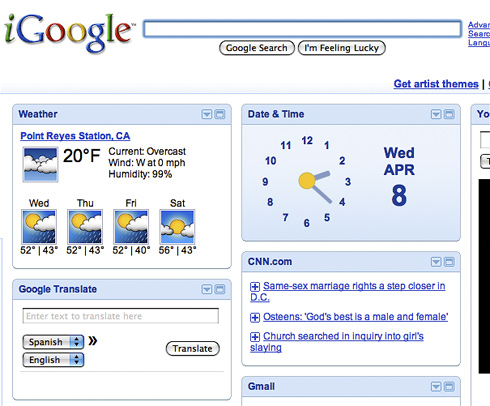

Just to see if the goofy temperature Google had listed around noon Tuesday was merely a brief aberration, I checked again at 2:22 a.m. Wednesday. By now the air outside had warmed up some, according to Google, but our springtime night was still 12 degrees below freezing. Meanwhile, my own outdoor thermometer showed an air temperature of just over 50 degrees.

Just to see if the goofy temperature Google had listed around noon Tuesday was merely a brief aberration, I checked again at 2:22 a.m. Wednesday. By now the air outside had warmed up some, according to Google, but our springtime night was still 12 degrees below freezing. Meanwhile, my own outdoor thermometer showed an air temperature of just over 50 degrees. By 2 p.m. Wednesday, my thermometer indicated the air outdoors had risen to 60 degrees, so I checked what Google was reporting and this time found Point Reyes Station sounding like a town in the tropics. If I were to believe Google, the temperature here had soared by 113 degrees in 26 hours. What is going on?

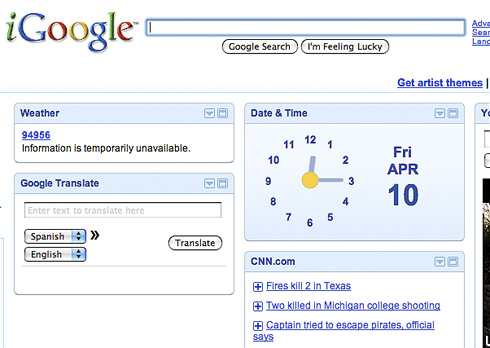

By 2 p.m. Wednesday, my thermometer indicated the air outdoors had risen to 60 degrees, so I checked what Google was reporting and this time found Point Reyes Station sounding like a town in the tropics. If I were to believe Google, the temperature here had soared by 113 degrees in 26 hours. What is going on? Addendum: By Friday, Google was reporting that in Point Reyes Station’s zip code, current temperature “information is temporarily unavailable.” I’d like to think that this blog had something to do with that, but I doubt it.

Addendum: By Friday, Google was reporting that in Point Reyes Station’s zip code, current temperature “information is temporarily unavailable.” I’d like to think that this blog had something to do with that, but I doubt it.

Closely following Friday’s discussion are oyster company owners Kevin and Nancy Lunny.

Closely following Friday’s discussion are oyster company owners Kevin and Nancy Lunny.

The “most common industries for males” working in West Marin, City-Data.com says, are: “construction, 17 percent; professional, scientific, and technical services, 10 percent; agriculture, forestry, fishing and hunting, 10 percent; educational services, 8 percent; accommodation and food services, 7 percent; health care, 5 percent; arts, entertainment, and recreation, 5 percent.”

The “most common industries for males” working in West Marin, City-Data.com says, are: “construction, 17 percent; professional, scientific, and technical services, 10 percent; agriculture, forestry, fishing and hunting, 10 percent; educational services, 8 percent; accommodation and food services, 7 percent; health care, 5 percent; arts, entertainment, and recreation, 5 percent.”