Sun 27 Oct 2013

My frantic flight from Latin

Posted by DavidMitchell under Dave Mitchell, Personal

[2] Comments

I was raised by Christian Science parents in Berkeley and attended Berkeley High School, but in the middle of my junior year I abruptly transferred to a boarding school in St. Louis. The story of how that came about illustrates what a teenager is capable of doing out of fear.

As a 16 year old, I often chafed at parental restrictions on my driving and staying out late, but at Berkeley High, I earned good grades in most subjects. Advanced Latin, however, proved to be a step too far. One afternoon in the fall of 1959, I went directly home after school in order to spend extra time studying for a Latin test only to realize the battle was lost. Given my grades so far, it was impossible for me to pass advanced Latin.

It was a frightening thought. I had never received less than a C in any class, and that alone had brought down my parents’ wrath. I had been grounded and had my allowance cut for a month. What might happen when I brought home an F was too awful to imagine.

It was obvious I couldn’t still be living at home when report cards came out. But what to do? Suddenly I remembered a Christian Science high school my parents had mentioned in glowing terms. It was called Principia and was safely located 1,800 miles away in St. Louis. I feared the school might be overly religious, but anything was better than facing my parents with an F in Latin.

I got up from my desk and went looking for my mother, who was in the kitchen cooking dinner. “I want to go to Principia,” I announced. My mother was startled, but given the pressures of trying to raise a headstrong teenager, she didn’t oppose my request. Instead, she took it up with my father, and a week before Berkeley High mailed home my grades for the fall semester, I boarded a train for Missouri, having no idea what I would find.

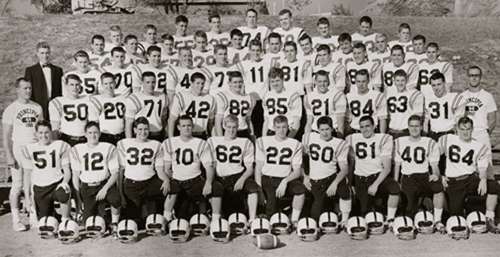

At Principia, where football players were generally smaller than at Berkeley High, I was big enough to play offensive tackle. I’m No. 74 in the middle of the back row. Because Principia’s sports program was far more modest than Berkeley High’s, I was able to letter in both football and track during my three semesters in St. Louis.

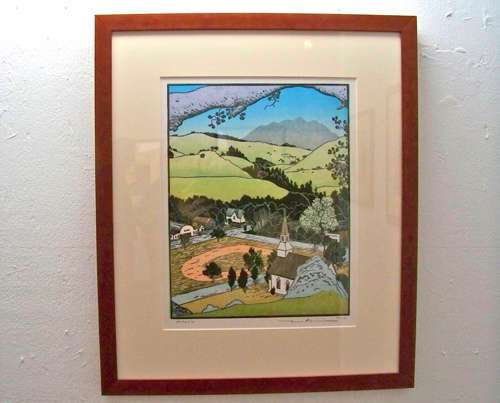

Principia Upper School had a newly opened, suburban campus on Clayton Valley Road, and the place had the pleasant charm of brick buildings and expansive lawns. Its religious atmosphere was about the same as in my home back in Berkeley.

A few days after I had been assigned a room and roommate, I got a call from my much-distressed parents. They had received my report card from Berkeley High and discovered I’d flunked Latin. How could I have done so badly when I’d been assuring them I was doing okay in Latin? “I’m as surprised as you,” I replied with feigned concern. “I must have blown the final exam. Everything seemed fine before then.”

My parents started scolding, but I interrupted to say I was being called away to Sunday dinner. Reluctantly, they said goodbye and hung up. In fact, there was nothing going on — other than my jubilation at being beyond their reach.

I sometimes practiced high jump barefoot. At Berkeley High, good jumpers were able to clear six feet. My best jump at Principia was five feet, six inches, but when I made it, that was enough to win the event, which was the last of the day in a track meet with John Burroughs Academy. When the high jumping finally got underway late that afternoon, each school’s total points happened to be the same, so my not-so-high jump won the meet for Principia.

Berkeley High had taught most courses a bit earlier than Principia did, so I frequently was already familiar with subjects when they came up in class. Nor did Prin offer any Latin. As a result, I was one of the top three students in my graduating class.

All this helped get me into Stanford University where circumstances eventually forced me to again take Latin. This time, however, my grades were three A’s and two B’s. Ironically, it was my best subject as an undergraduate. How could that be?

First, thanks to my classes at Berkeley High, I was already familiar with basic Latin. Second, the night before each final, I sat down with a Latin-English dictionary and practiced translating passages from Caesar’s Gallic Wars, The Aeneid, etc. The passages were typically ones the professor had emphasized in class, and I figured some of them were likely to be on the exam. That quickly turned out to be true. Three times I managed, with the help of a dictionary, to translate every passage on a final exam just before I took it. My flight from Latin was over.