Wed 25 Jul 2018

A dandy cat among the dandelions

Posted by DavidMitchell under General News, West Marin nature, Wildlife

1 Comment

Looking out the kitchen door earlier this week I saw a handsome bobcat among the dandelions.

It’s been a periodic visitor around Mitchell cabin, but of late its visits have become more frequent. When the bobcat’s around, it spends most of its time hunting gophers, often sitting or standing like this waiting to pounce. I can only assume it’s seen a gopher head pop out of the dirt for a moment or that it can hear a gopher scratching underground.

A smelly surprise this past week was a triad of young skunks marching in close formation back and forth across the hill. I have no idea why they arranged themselves in that fashion, but it was fun to watch.

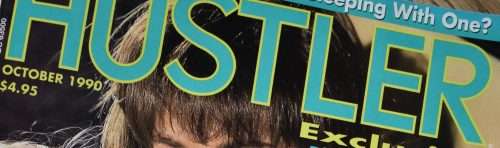

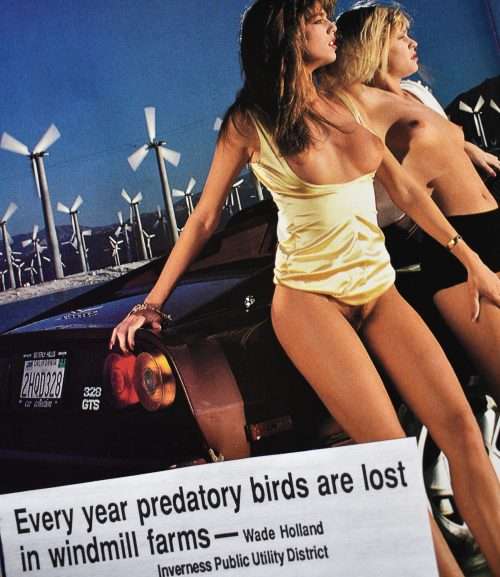

But the biggest surprise I encountered this week was in a 28-year-old copy of Hustler magazine that I came upon.

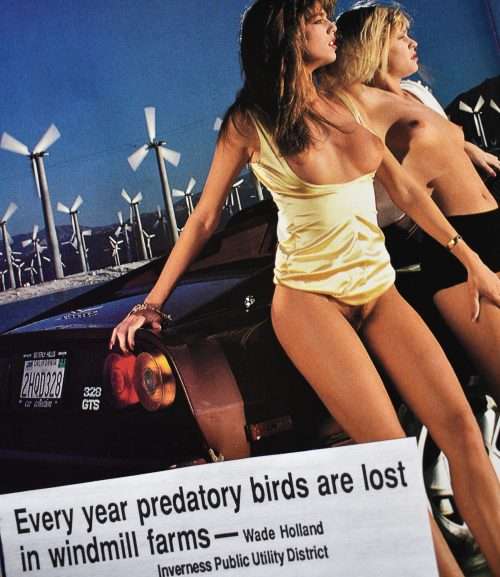

As part of a photo feature in the men’s magazine, there was a picture of a wind farm with a couple of scantily clad young ladies standing in front of it. All that was typical Hustler. The odd part was the accompanying quotation from Wade Holland of Inverness, who back then was manager of the Inverness Public Utility District.

Before I asked Wade today about the quote, he was unaware he’d been in Hustler and found the revelation quite amusing. Wade said the remark dated from an abandoned proposal by IPUD directors to use windmills to generate part of the town’s electricity. God only knows how the magazine came upon his comment. Did someone at Hustler have a subscription to The Point Reyes Light (where coincidentally Wade is now copy editor)?

Less amused was a different Wade B. Holland. When I initially tried to call West Marin’s Wade B. Holland, I found the number I was using had been changed. I then searched online for another number and found one that looked like it might be his cellphone.

I called the number, and when a man answered, I asked if he was Wade Holland. He said he was, so I asked him if he were aware he’d been quoted in Hustler back in 1990. The man, who turned out to be in North Carolina, was astounded.

And when I read the quotation to him, he become a bit indignant, saying he was not the Wade B. Holland in that magazine. So I said goodbye and left him to tell his friends about the bizarre call he had just received from California.