The Mexican holiday Dia de los Muertos (Day of the Dead) was observed Saturday evening in downtown Point Reyes Station. It’s a day set aside each year for special remembrances of friends and relatives who have died.

Meanwhile up the bay, Tomales Regional History Center on Sunday opened a well-attended exhibition, “The Region’s Lost Buildings: Their Stories and their Legacies.” More about that in a moment.

A Dia de los Muertos altar in the Dance Palace held dozens of photographs of deceased family members and mementos of their lives.

Saturday’s celebration began with a procession from Gallery Route One to the Dance Palace. These young ladies wore angel costumes and looked very sweet while some celebrants wore Halloween costumes which were downright ghoulish.

Ana Maria Ramirez, the de facto matriarch of the Latino community around Point Reyes Station, spoke in English and Spanish about Dia de los Muertos. The event was organized by Point Reyes Station artist Ernesto Sanchez, who also created the altar. The Dance Palace sponsored the event with financial support from Marin Community Foundation.

A variety of excellent Mexican food drew a long line to the serving table.

Local singer Tim Weed and his partner Debbie Daly (in white) led some impromptu singing in the Dance Palace.

For many in attendance, including Mary Jean Espulgar-Rowe and her son Joshua, it was a family event.

Elvira de Santiago of Marshall paints the face of Ocean Ely, two and a half, of Point Reyes Station.

Carrie Chase and Diego Chavarria, 10, of Point Reyes Station showed up in elegant costumes. Here Diego waits to have his face painted.

And while all this was going on, photographer Eden Trenor (left) of Petaluma and formerly of Point Reyes Station, was having an opening in the Dance Palace lobby for an exhibit of her works. With her is Dan Harrison, a printmaker who owns a gallery in Olema.

This photograph of ponds is part of Trenor’s show, which is called “For the Yes of It.” _______________________________________________________________

“The Region’s Lost Buildings: Their Stories and their Legacies,” which opened at the Tomales Regional History Center Sunday, is also a photographic exhibit for the most part, but the photos are far older.

Curating the exhibition was Ginny Magan of Tomales, and she did an excellent job, both in her choice of pictures to display and in her captions for them.

The narrow-gauge railroad depot in Marshalls, as Marshall used to be called. The Shields store to the right of the depot still survives and now belongs to Hog Island Oyster Company. “This image of Marshall’s depot shows a style typical of small, early train stations across the country, with its board-and-batten siding and deep eaves,” its caption notes.

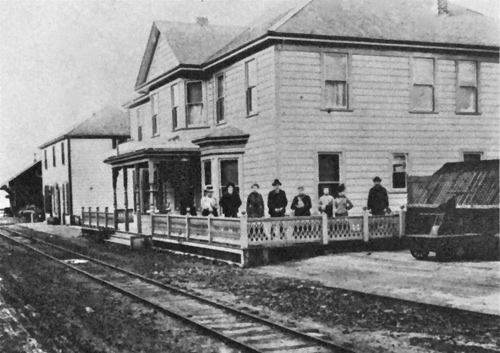

The Bayview Hotel, which once stood in this spot on the shore of Tomales Bay, was built by the Marshall brothers in 1870 and was frequented by fishermen and hunters.

When it burned in 1896, the Marshall brothers had the North Coast Hotel (above) constructed on the site. “As the photo shows,” the History Center points out, “the building was a few feet from the railroad tracks.

“The hotel was knocked into the bay by the 1906 earthquake, but pulled out and repaired by the owners, Mr. and Mrs. John Shields.

“Except for its use as military housing during the Second World War, the building remained a hotel under several proprietors until it caught fire in 1971. The 25 guests, all the employees, and owner Tom Quinn and his family got out safely, but the hotel, with only its brick chimney standing, was a complete loss.”

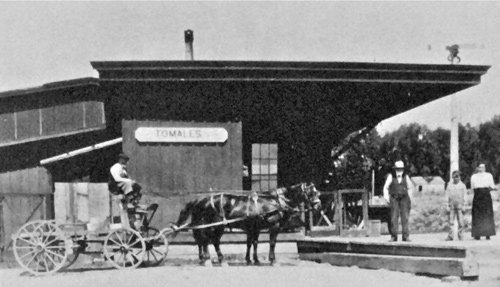

“The depot at Tomales was unusual,” according to the History Center’s caption. “Because of its low-pitched roof, it resembles something built a century later. All Tomales railroad buildings were painted a brick red.

The aptly named hamlet of Hamlet, another stop on the North Shore Railway line, was a village from 1870 to 1987, when the National Park Service bought it.

“Hamlet’s namesake was John Hamlet, a dairyman from Tennessee who purchased the site with gold coin in 1870. He left little but his name. The next owner, Warren Dutton, developed Hamlet as a railroad stop that the Marin Journal described as ‘one of the most inviting places on the bay for aquatic sports.’

“To most of today’s locals, the name Hamlet is connected with the Jensen family, who purchased the land in 1907, and developed and inhabited the village over 80 years and four generations. By 1930, the Jensens were establishing Hamlet’s well-known connection with oyster farming.

The Tragedy of Hamlet.

“In 1971, third-generation matriarch Virginia Jensen was left a widow with five children. She, and eventually they, carried on, though maintaining the oyster farm, its retail components, and the property’s buildings was clearly a struggle.

“A 1982 storm all but obliterated the oyster beds. ‘I never planted [oysters] after that; that was my last tally-ho,’ remembered Mrs. Jensen. In 1987, she sold the site to the Park Service, which then looked the other way as vandals and the elements savaged it. In 2003, the Park Service demolished the last of the buildings.

Highway 1 is the main street of Tomales where it’s known as Maine Street.

“Trotting down Maine Street toward First c. 1890. Originally the Union Hotel occupied this site; after it burned this group of small buildings housed a saloon, one of six or eight in the town, a billiard room and Sing Lee Washing and Ironing. Today the Piezzi Building is at this corner.”

“On a windy day in May 1920, the Plank Hotel caught fire. Despite the best efforts of townspeople at least 16 buildings burned to the ground, two dwellings and most of the town’s commercial center south of First Street.”

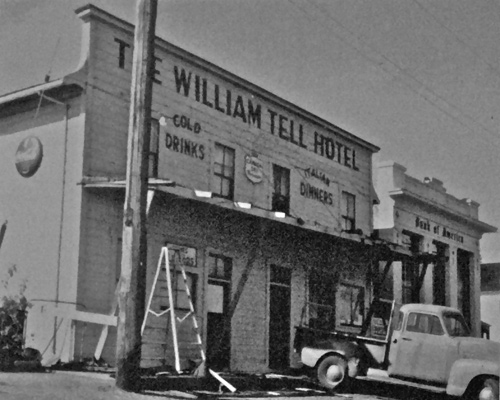

“The William Tell was established as a hotel and saloon in 1877. The original building burned in the 1920 fire but was rebuilt within the year. This photo was taken in the mid-1950s.

“The Fallon Creamery, built near the end of the 19th century, used state-of-the-art, steam-operated machinery. The creamery exhibited a 500-pound wheel of cheese at the 1894 California Midwinter International Exposition in San Francisco.” ________________________________________________________________

By the end of the weekend I was again thanking my lucky stars to be living in West Marin. Everybody had been on their good behavior, even the cops.

By the end of the weekend I was again thanking my lucky stars to be living in West Marin. Everybody had been on their good behavior, even the cops.

When a sheriff’s deputy needed to use his patrol car to create a buffer for the DÃa de los Muertos procession marching down Point Reyes Station’s main street, I walked over and with feigned indignation exclaimed, “They’re all jaywalking.” The deputy replied with a laugh, “They are all jaywalking. And everyone is going to get a ticket.” And soon he drove off.

What a contrast with police in Saint George, Utah. At least according to the Daily Kos website, police last week raided a Halloween party at a family fun center simply because the event included dancing.

What a contrast with police in Saint George, Utah. At least according to the Daily Kos website, police last week raided a Halloween party at a family fun center simply because the event included dancing.

One can only imagine how St. George’s police would have reacted to the Aztec Dancers (left) in Point Reyes Station.

They weren’t just dancing, they were dancing on the main street.