Just over a year ago, Tomales Regional History Center published my second book (coauthored by Jacoba Charles) The Light on the Coast: 65 Years of News Big and Small as Reported in The Point Reyes Light. The third printing is almost sold out, and it may soon be time for a fourth.

To whet the appetite of those of you who haven’t yet picked up the book, here’s a column from it that was originally written 30 years ago when these ruminations were in print labeled “Sparsely Sage and Timely.” Back then, The Light was published in Point Reyes Station’s Old Creamery Building with the newsroom on the second floor.

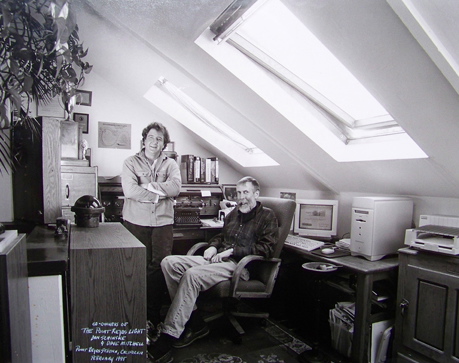

The Light’s former newsroom with my partner Don Schinske standing and me sitting at my desk. Back then I wrote and edited text on a computer but wrote headlines on an old-fashioned, standard typewriter and then hand-carried them to the typesetter downstairs. © 1998 Art Rogers/Pt. Reyes, who contributed 10 photos to “The Light on the Coast.”

It’s late in the evening, and I’m sitting at a rolltop desk in the newsroom listening to a dog barking a block or two away. Every minute or so, I can hear a car come down Highway 1 into town and turn the corner by the bank. Once in awhile, a car heads up the hill, probably someone who just stopped in town for a drink before heading home.

When I first arrived in Point Reyes Station in 1975, I slept for a couple of months in the newsroom of the old Light building [across the street from today’s Whale of a Deli]. Despite being at a bend and intersection of a state highway, the spot was reasonably tranquil, at least after midnight. Oh, there’d be a brief flurry of shouting when the bars closed and the sound of unsteady feet scuffing past the window, but for a place to spend the night, a room on Point Reyes Station’s main street wasn’t that bad.

When I was in college and had yet to live in a small town, I chanced to read Winesburg, Ohio, Sherwood Anderson’s sketches of small-town life. In one of the tales, The Teacher, Anderson describes a late evening when there are only three people awake in Winesburg.

Naturally, one of the three was a reporter in the newsroom of the town’s weekly newspaper who pretended to be at work on the writing of a story. At last, the reporter too goes home and to bed. “Then he slept,” wrote Anderson, “and in all Winesburg, he was the last soul on that winter night to go to sleep.”

As a college student used to cities and suburbs, I found the concept of a town where no one was awake so strange that I briefly wondered if such a place were possible. Now, 20 years later, I find myself living in a town where on occasion late at night I probably am the only person downtown who isn’t asleep.

Of course, there are some nights when the tranquility of even this sleeping town is disturbed. A few years ago, Michael Jayson told me at the time, he had been asleep in an apartment over the old Dance Palace [where Cabaline is today] when he was awakened by the thunder of hooves below his window on Third Street.

A dog had gotten into rancher Waldo Giacomini’s pasture [now the Giacomini Wetlands] and began to worry a herd of cows, which then gave chase to the dog, crashing through a barbed-wire fence in their pursuit.

The next morning, Jayson told in amazement of having seen the stampede gallop up Third to Point Reyes Station’s main street and then turn east. At the T-intersection where the main street ends in front of Cheda’s Market, the herd wheeled around and headed back west.

As it happened, a fight had spilled out of the Western Saloon and into the intersection at Second Street where it had caught the eye of a bartender across main street at the Two Ball Inn [now the Station House Café. He called sheriff’s deputies, who had just arrived to break up the brawl when the stampede did it for them.

With a herd of cows galloping toward them, the two brawlers, along with onlookers, scattered. After the stampede had passed, however, the brawlers returned to the intersection only to have the stampede come through again on its second pass.

This time as the crowd dashed for safety, the two combatants kept on running, as did a number of Giacomini’s cows once the stampede reached the west end of main street. It was two days before the rancher got them all rounded up again. “I wish some people would keep their dogs tied up,” he grumbled to me afterward.

Down the street, the dog is barking again,probably bragging about the night when he alone provoked 50 head of Waldo Giacomini’s dairy cows to stampede through the middle of town. April 11, 1985