Wed 18 Apr 2007

Nature’s Two Acres Part XIII: ‘Who’s the Head Bull-Goose Loony Around Here?’

Posted by dave under Point Reyes Station, Marin County, West Marin nature, Wildlife, Photography, agriculture

[3] Comments

I need merely to look out my cabin windows to see it all around me — among the deer, horses, and red-winged blackbirds, among the raccoons, steers, and bluejays. It’s the unending struggle by each species to maintain its pecking order.

The pecking order — which is sometimes called “dominance hierarchy” or “social hierarchy” when talking about humans and other mammals — takes its common name from the fact that it was first observed among poultry.

The pecking order — which is sometimes called “dominance hierarchy” or “social hierarchy” when talking about humans and other mammals — takes its common name from the fact that it was first observed among poultry.

As Wikipedia explains, “The top chicken is one which can peck any chicken it wants. The bottom chicken is one that lets all the other chickens peck on it and stands up to none. There are chickens in the middle, who peck on certain chickens but are, in turn, pecked on by other chickens higher up on the scale.”

Like other young animals foxes play fight to establish dominance. I photographed these red foxes across my fence on neighbor Toby Giacomini’s land. The fox described below was the locally more-common gray fox.

.

You can observe pecking orders in prisons and schoolyards. In his 1960 novel One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, Ken Kesey (1935-2001) portrays a sane man, RJ McMurphy, who cons his way into a mental institution to avoid a short prison term for petty crimes. Once in the institution, McMurphy immediately asks his fellow wards America’s eternal question, “Who’s the head bull-goose loony around here?

Pecking orders are more pronounced among some species than others, I’ve observed. With red-winged blackbirds, for example, maintaining their chosen spot at the feast of birdseed on my railing is more important than eating it. Brown towhees and Oregon juncos, on the other hand, worry far less about who’s at the head of the table.

I once asked Point Reyes Station naturalist Jules Evans why some birds are more aggressive toward their own species when feeding than are other birds. Evans said he wasn’t certain but theorized that birds whose diets are limited to certain food would likely protect it more aggressively than birds that eat a wider variety of foods.

While social hierarchies are supposed to exist within a species, there are obviously similar hierarchies among species.

The cutest little roof rat you ever did see stretched like a first grader at a drinking fountain to get a drink from my birdbath at twilight Thursday.

Last week, I was watching a towhee pecking at a scattering of birdseed under my picnic table when a roof rat ran out from behind a flowerpot and drove the towhee off. I’d never seen such a thing before, but the towhee seemed unfazed. It merely hopped three feet away and started in on another scattering of seeds.

To some extent size determines which species dominates which. A possum will scurry off if a raccoon shows up. But as I observed Tuesday night, a raccoon will flee a much-smaller fox.

Usually, confrontations between raccoons themselves are limited to growling and — like blackbirds —fluffing up to look bigger.

But I’ve also seen raccoons fight, and they were savage.

Although raccoons have fearsome canine teeth, the little gray fox I saw Tuesday clearly had a much-larger raccoon buffaloed — if you can stand the metaphor. And even if you can’t, this column is over. But if someone knows why a raccoon would be afraid of a fox, please send in a comment.

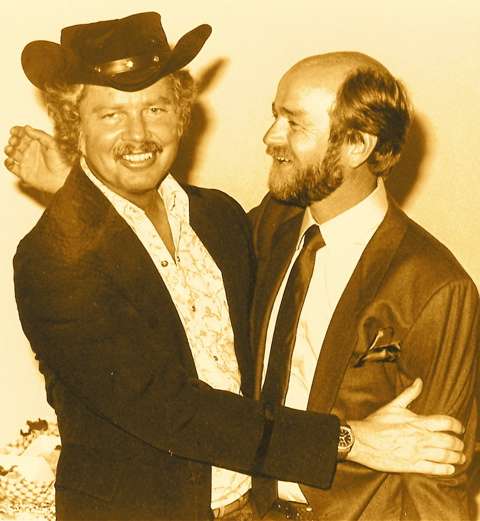

SparselySageAndTimely.com extends a warm “Happy Birthday!” to restaurateur Pat Healy of Point Reyes Station (left), who topped 80 on Wednesday.

SparselySageAndTimely.com extends a warm “Happy Birthday!” to restaurateur Pat Healy of Point Reyes Station (left), who topped 80 on Wednesday. Also celebrating her 80th birthday is Missy Patterson of Point Reyes Station, who will turn 80 on Sunday. For 24 years, Missy has run the front office of The Point Reyes Light, where she is circulation manager.

Also celebrating her 80th birthday is Missy Patterson of Point Reyes Station, who will turn 80 on Sunday. For 24 years, Missy has run the front office of The Point Reyes Light, where she is circulation manager. .

. .

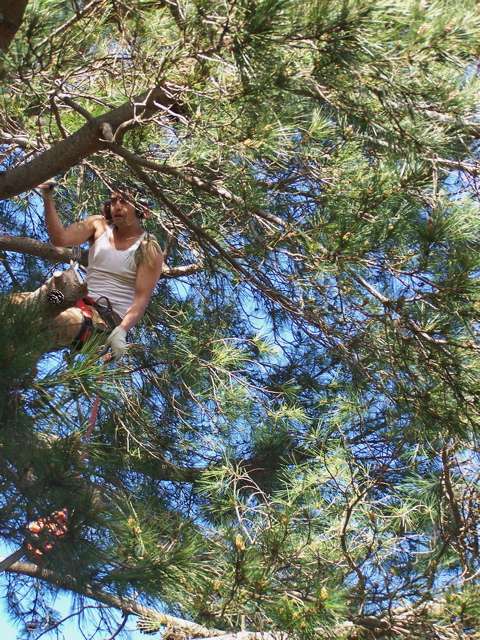

. The common Spanish nickname “Nacho” (at right) was easy for me to check on. It’s merely a shortened form of “Ignacio,” sort of like “Robert” shortened to “Bob.”

The common Spanish nickname “Nacho” (at right) was easy for me to check on. It’s merely a shortened form of “Ignacio,” sort of like “Robert” shortened to “Bob.”

He also snorted cocaine with gonzo journalist Hunter Thompson, the basis for the character Duke in Doonesbury. Seen here in a

He also snorted cocaine with gonzo journalist Hunter Thompson, the basis for the character Duke in Doonesbury. Seen here in a  In March 1985, the film premiered at “a gala opening party,” in the words of the invitations we in the press received.

In March 1985, the film premiered at “a gala opening party,” in the words of the invitations we in the press received.

I threw several crackers on my deck, and the raccoon returned so I could give it a closer look.

I threw several crackers on my deck, and the raccoon returned so I could give it a closer look. Keith’s guess was that the raccoon had poked herself in the eye — possibly while nosing around in a hole. Made sense to me although I wouldn’t rule out a fight. I’ve seen raccoons fight, and they are ferocious in battle.

Keith’s guess was that the raccoon had poked herself in the eye — possibly while nosing around in a hole. Made sense to me although I wouldn’t rule out a fight. I’ve seen raccoons fight, and they are ferocious in battle.

“This time [then-Interior Secretary] Gale Norton (at right) and the Park Service said, ‘It’s been a very good commission for 29 years, but we don’t need it anymore,’” noted former Commissioner Amy Meyer in an interview I conducted for Marinwatch.

“This time [then-Interior Secretary] Gale Norton (at right) and the Park Service said, ‘It’s been a very good commission for 29 years, but we don’t need it anymore,’” noted former Commissioner Amy Meyer in an interview I conducted for Marinwatch. Congresswoman Lynn Woolsey (at right), who represents West Marin, did introduce legislation to resurrect the commission, and it was attached to a House bill being pushed by now-Speaker Nancy Pelosi and others to acquire land in San Mateo County for the GGNRA.

Congresswoman Lynn Woolsey (at right), who represents West Marin, did introduce legislation to resurrect the commission, and it was attached to a House bill being pushed by now-Speaker Nancy Pelosi and others to acquire land in San Mateo County for the GGNRA. Meyer said she and other people went to Congresswomen Pelosi (at left) and Woolsey and asked that they drop the advisory-commission legislation.

Meyer said she and other people went to Congresswomen Pelosi (at left) and Woolsey and asked that they drop the advisory-commission legislation.

Before flying to Italy, however, McEvoy sent Castelli water and soil samples from her ranch, along with weather records, and “he decided, yes, we could do it,” she said.

Before flying to Italy, however, McEvoy sent Castelli water and soil samples from her ranch, along with weather records, and “he decided, yes, we could do it,” she said.

Traps are more effective in controlling roof rats.

Traps are more effective in controlling roof rats.